This post is part of a series of guest posts by the authors contributing to Triumph Over Tragedy. They will spontaneously appear over the next few weeks. I have asked authors to write about how life experiences affect their writing (or reading).

Thanks to the authors for taking time out of their lives to write these guest posts.

As always, you can check out more about Triumph Over Tragedy, or donate here.

(On a personal note, I want to thank Mark for writing this post and letting me use it on my website. His post from my Special Needs in Strange Worlds series – which you can find on my Guest Posts/Interviews tab – still resonates profoundly with me. He has some amazing knack for touching me on an incredibly deep level, so I’m thrilled to add this post to my list of mind blowing guest posts that have been, and will be featured on my website.)

—–

About the Author

About the Author

Mark Lawrence is married with four children, one of whom is severely disabled. His day job is as a research scientist focused on various rather intractable problems in the field of artificial intelligence. He has held secret level clearance with both US and UK governments. At one point he was qualified to say ‘this isn’t rocket science … oh wait, it actually is’.

Now, onto Mark’s incredible post….

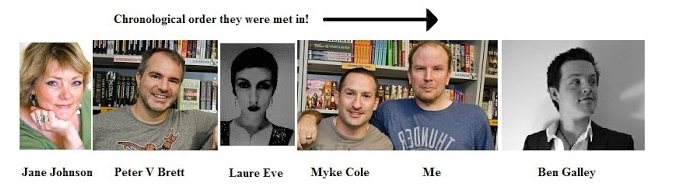

I don’t know many writers. I’ve met five in total, and they were a disperate handful. All of them verbally dexterous, all of them clever and thoughtful, but beyond that a diverse bunch.

Our writing experiences seem to be equally varied. Some of us agonize over each element of plot and prose, others dash it down and move on. Some focus on action, some on character, others build world’s first and the populate their stage.

What I think might unite us as a common core is that writing is hard – you need to push against an invisible something that doesn’t want to move, and doing so exhausts some secret muscle you didn’t know you had. It requires you to exercise both your imagination and your emotions, stretching both to a degree where it starts to hurt. And beyond that, the sharing of that writing – which undeniably you have put something of yourself into, something personal and generally hidden – that sharing requires courage.

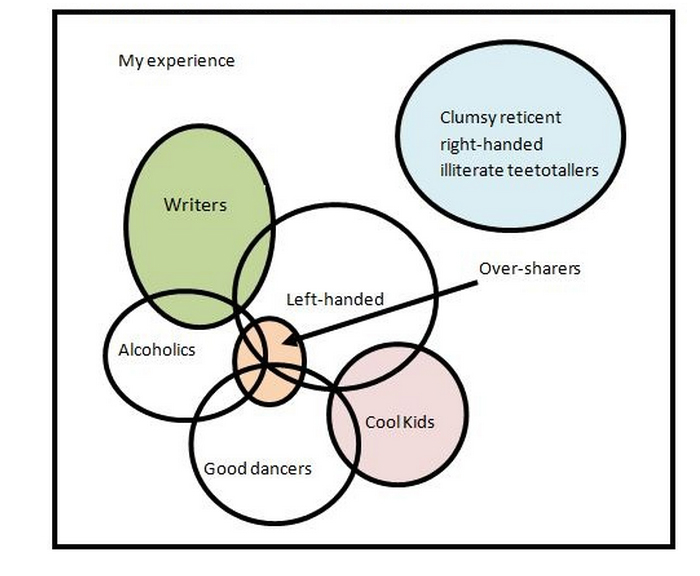

There are certain people that like to over-share. People who will assault strangers with their intimate personal details, people who with the slightest provokation will shine an unwanted light on the mechanics of their close relationships, or elaborate upon the most trivial and embarrassing of their medical complications. My limited experience of writers suggests that we’re not those people. Putting ourselves out there isn’t an instinct – it’s a gamble, a risk.

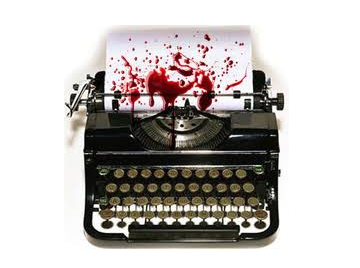

Ernest Hemmingway famously said: “There is nothing to writing. All you have to do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.” That is certainly an overstatement for me, but then again I won’t be counted a giant of literature a half century after I’m dead. It’s true though that the occasions when it has felt more like bleeding are the ones that led to passages of mine that are most talked about and quoted.

To do that, and then put it up for rejection, and failing rejection, to have it published and exposed to ridicule, requires courage. Just because you have felt something passionately, and what you wrote resonates back with you when you read it – does not mean that it will echo with others or that it is well written. It is a risk.

The penalty is nebulous and can be dismissed as insubstantial, but it has sharper edges than any reply that girl you asked to dance at the school disco ever gave you.

To the theme of this post – Sarah invited a triumph over tragedy vibe, an insight into how life experience lensed into writing practice.

Clichés exist because there are things that are so true they bubble spontaneously from many sources. Clichés aren’t wrong, just over used. It’s a cliché to say that surviving a tragedy gives you a new perspective. The man still standing after a building has fallen around him, or reprieved from some terminal condition, will tell us that the world looks different, that trivial concerns now seem exactly hat, trivial, and will no longer tug at him. He will concentrate on what matters from now on, walk taller, be a better person. That’s how we feel at such times. There’s a half-life to it though. Good intentions slip, resolutions slide, and the world catches hold of us again by degrees, sinking innumerable petty little hooks into us.

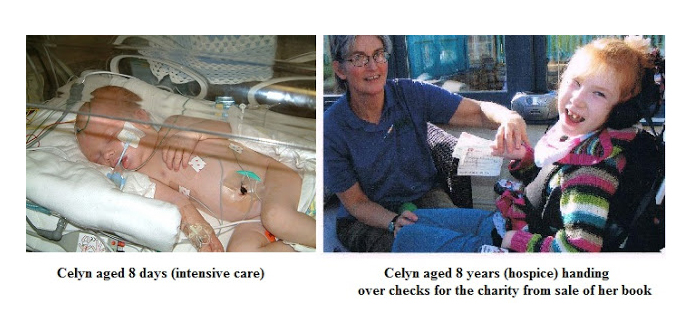

My tragedy was largely vicarious. It’s my daughter’s tragedy. There’s a reaction against using that word in the same breath as disability because it can seem to belittle the person, to focus on what’s been lost rather than what skills and potential they have. I agree with that sentiment. My daughter was severely disabled by complications during her birth but she loves life, is happy as often as she can be, and is a tremendously valuable and wonderful person. She even has a picture-book in the semi-finals of the Goodreads Choice Award! But, none of that changes the fact that I will always feel that the randome chance that stole her ability to speak, to walk, to hold, to eat, to sit, to see a horizon, and to grow without pain was a tragedy.

She is not tragic – what happened to her was a tragedy.

And some small part of it was my tragedy too – and it made me feel like the man in the cliché. And whilst the world has stolen away much of that feeling of invulnerability – that false conviction that you’ve faced the worst and nothing could now hurt you – I retained some small measure of that courage. And it’s that courage, bolted to my original marginal stock, that tipped my hand, made me send my manuscript out, and made me smile whenever I got a bad (or sometimes hateful) review, knowing that in the grand scheme of things, and indeed in pretty much every minor scheme of things too, it really didn’t matter much. What mattered was that I’d said what I had to say, I’d drawn my line in the sand, and whether it lasted, whether it was noticed, whether that girl adt the disco said no and her friends giggled behind their hands – I had taken my chance and would not regret doing so.

One Responses

If to write is to bleed, then Mike Lawrence not only must have the constitution of a stallion but also heme fluid so potent that leeches would get drunk on the second sip, and mosquitoes who partook would no doubt begin glowing and experience spontaneous combustion from an overdose of awesome.

As per usual, I am humbled by Celyn’s story and thrilled her picture book, Wheel Mouse, has been able to bring joy to so many.

And if there’s one thing that’s near and dear to my heart it’s Venn diagrams. This one felt like a betrayal. With no overlap between writers and good dancers, I felt the chilling vibration of nothingness that threatened to blink me out of existence. Who am I to gainsay the power of the almighty Venn? In my audacity I will say that improvisational dancing is creativity in motion. Writing is creativity in language. Given that bridge, I will throw down the gauntlet and say it is possible for writers to be good dancers. As evidence for that as well as my own audacity I will submit my BookDancing channel on YouTube. Seek it out, ye bold.